You don’t create an ethical culture within an organisation by imposing rules – but leading by example

by Peter Taylor-Whiffen

“Do the right thing,” counselled the 19th-century American writer Mark Twain. “It will gratify some people – and astonish the rest.”

Ethical behaviour really shouldn’t be a surprise or a shock to clients, but recent events on Wall Street suggest it might take more than compliance rules to create an ethical culture in financial organisations.

In September 2022, 11 Wall St banks and brokers – including Barclays, Goldman Sachs and UBS – were fined a total of US$1.8bn by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission after what amounted to a systemic consistent breaching of security rules by illegally discussing business deals and trades on their personal, unmonitored mobile phones.

In response to this, SEC chair Gary Gensler stated: “Finance, ultimately, depends on trust … [and] the market participants we have charged have failed to maintain that trust.”

That is just one example in a string of recent publicly exposed transgressions by financial firms. In June 2022, Dublin-based AIB was fined almost €100m for regulatory breaches in its treatment of tracker mortgage customers, which had caused “unacceptable harm” to customers over 18 years. That same month, Credit Suisse was ordered by the Swiss Federal Criminal Court to pay fines and compensation totalling US$22m after one of its employees was found guilty of laundering money for a Bulgarian drug gang.

In many cases, these transgressions are down to individual unethical behaviours, but they do raise questions about the cultures that allowed them to happen, as well as a wider query: if rules don’t work, is it time for financial firms to look beyond compliance and regulations and consider instead how to introduce an overall ethical culture that drives their employees’ behaviour? How do you make someone do the right thing?

One bad apple

“It’s interesting that the FCA has shifted its guidance from ‘fair outcomes’ towards ‘good outcomes,’ says corporate philosopher in residence at Bayes Business School, Roger Steare, who develops corporate culture and ethical programmes for global organisations. “It’s finally realised that the purpose of the financial services business is to do good and create a good outcome for customers – and unless they do it also for their shareholders, suppliers and colleagues they won’t sustain their business.”

Public perception is a challenge. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, films such as The Wolf of Wall Street and The Big Short unhelpfully furthered the erroneous notion that financial professionals had no moral compass – although both of those movies were based on real events. The BBC’s recent drama series Industry, about a fictional investment bank, further promotes the idea that dog-eat-dog self-interest is the only way to succeed and that compliance rules put in place to protect customers are an inconvenience to be worked around. On the other hand, for the most famous celluloid example of a financial services professional acting selflessly and ethically, you have to go back to 1946 and George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life – a film that initially flopped.

So, where do you start?

Morality in our DNA

Most people naturally understand right and wrong without, in many situations, the need for rules. This does not mean doing away with rules – such guidance is still essential, but in and of themselves rules are by definition about power, says Roger, and when taken in isolation people follow them because of fear, not through moral choice. Therefore, he argues, to create an ethical culture you need an organisational setup that reflects universally shared moral values which Lawrence Kohlberg, a legendary US psychologist, identified we develop as we move from childhood into adulthood.

When you treat adults like children, they start to behave like children and don’t take responsibilityAccording to Marshall Schminke, professor of business ethics at the University of Central Florida and former member of the Washington DC-based national US Ethics and Compliance Initiative, Kohlberg’s suggestion was that when we’re children, what is right and wrong is defined by “what mom and dad tell us,” and that as people mature they come to view themselves as part of a social system with expectations and norms. Schminke adds that any ethical culture needs to be based on these norms. A good simple set of universally accepted social rules is therefore an important part of moral philosophy, says Roger, “but in business ethical ‘rules’ can give the message ‘I’m not interested in your moral conscience, I’m going to tell you what’s right or wrong’.” That, says Roger, puts us back into Kohlberg’s moral infancy: when you treat adults like children, they start to behave like children and don’t take responsibility – which means when they meet a new ethical situation where the rules don’t tell them right from wrong, they don’t know how to work it out.

But, while those at the top of the organisation often address ethics by grandstanding platitudes around core values (well-meant platitudes, but platitudes nonetheless), an employee who, say, wants to beat their colleague to a promotion, or needs to hit target to get a bonus that will pay their bills that month, will have a different personal motivation to succeed – and may therefore be tempted to bend a few rules along the way.

Cultural evolution

If you can’t bring people into line by telling them how to behave, how do you imbue in all your employees an instinctive awareness of the right way to do things? “Ethical cultures tend to evolve,” says Roger, adding that even if there’s a catalyst that forces companies to make sudden cultural changes, such as a new CEO, it’s not about telling employees what their moral values should be. Rather, it’s about discovering that the collective moral value of an organisation is “generally consistent and coherent”.

Of course, there are exceptions, and there’s always a minority, and in senior positions what Roger calls a “significant minority of people with psychological disorders such as narcissism, Machiavellianism and various degrees of pathology” – but the natural resolution for this situation in a positive ethical company is that these people don’t feel they fit and move on. Former Barclays boss Anthony Jenkins famously encouraged such employees to leave, sending a memo to staff stating: “There might be some [of you] who don't feel they can fully buy in to an approach which so squarely links performance to the upholding of our values. My message to these people is simple: Barclays is not the place for you.”

Many companies give their staff ethics and compliance training – but many companies get this wrong, and statistics suggest many see it as more an optional add-on than a must-have. Research by Statista in 2022 finds companies have a list of challenges that make it hard to deliver, topped by limited hours for training (44%), insufficient resources (37%), difficulty covering topics important to their organisation (32%) and learner fatigue (28%), a list of gripes that don’t sound indicative of a collective will to put ethics at the heart of business.

That said, ethics is becoming more central to business practices around the world, according to the Institute of Business Ethics 2021 Ethics at work survey, which looks at employees’ perceptions of their workplace culture. The study of 13 countries on four continents finds 86% of employees believe honesty “is practised always or frequently in their organisation”, up from 79% in 2018.

The survey’s country results show that the US scores the highest, with an ‘ethics at work index’ of 84.8. This reflects scores in four main areas:

- Ethical example set by line managers

- Responsible business dealings in all areas

- Ethics of senior management

- Accountability for those who break ethical rules

South Africa comes second with an index of 84, followed by Switzerland (83.2), Australia (82.4) and New Zealand (81.2). On the other end of the scale is Portugal (76.6), closely followed by Italy (79.2) and the UK (79.6).

But across all jurisdictions, the study finds that an ethics programme is insufficient to stamp out unethical behaviour, with 48% saying their line manager rewards employees who get good results even if they deploy unethical practices to do so.

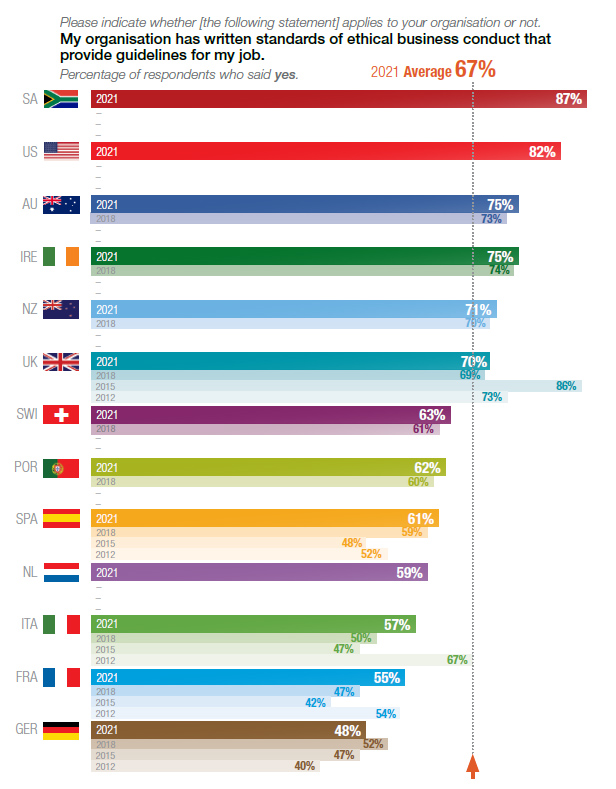

How common are codes of ethics?

Institute of Business Ethics: Ethics at work survey 2021

Commenting on the survey's results, Dr Ian Peters MBE, director of the Institute of Business Ethics, says: “As we’ve set out in our good practice guide, there are two fundamental stages for an organisation to create an ethical culture. Firstly, they have to define what an ethical culture looks like for them. That differs between businesses and setting that definition is essential in ensuring the right values and practices are being promoted to the workforce.

“The other fundamental is measurement. Companies will fail in maintaining what they perceive to be an ethical culture without clear, consistent and regular assessments in place to ensure values and practices are adhered to.”

Not just lip service

The fact that unethical behaviour remains in some firms does not surprise Marshall Schminke. “Most companies work pretty hard at trying to instil a culture of ethical thinking and many training programmes do that, but turning people into sophisticated, ethical thinkers is not enough to convert to ethical behaviour,” he says. “There are two other necessary components that my research shows get little attention – ethical behaviour also requires an emotional connection, as well as a belief your actions will be successful.”

Marshall’s findings are that those receiving the training need to care about the people their actions will affect – if you don’t care about your employees, colleagues, customers and community, they are morally irrelevant to you and therefore there is no point to doing right by them. Not only that, but the workers he studied were only likely to follow through with action if they thought it would work. “People need to know their company has their back, that they are supported – they need safe easy access to hotlines and supervisors they can trust. You need all three of those components for ethical training to succeed and if any one of them is zero, the whole thing goes to zero.”

People need to know their company has their back, that they are supported

His research also identifies another crucial difference in the success or failure of ethical cultures. While board and executive members sign up for courses, and shop-floor level workers undergo training, Marshall found a gap in the education of middle managers – which he found curious, as most workers with an ethical dilemma will seek help from their immediate supervisor.

“This is vital to an organisation’s embracing of ethical responsible culture,” he says. “If you have an organisation that’s demonstrated it is truly rotten at the top, the necessary first step is to replace the head. You could sack the top management team but if you don’t educate at supervisory level, nothing will change. The effect supervisors have on a company’s culture, the response that individual workers get when they have a problem, is greater than the co-workers and top-level executives combined.”

A healthy culture in law

As businesses have understood the value in creating an ethical workplace, so various regulations and guidelines have developed to support this:

The Senior Managers & Certification Regime – introduced by the FCA in 2015, replaces the Approved Persons Regime and aims to establish healthy cultures and effective, ethical governance by making employees at all levels responsible for their actions.

Conduct Risk – the FCA expects firms to “seek good behaviour across all aspects of their organisation and develop a culture in which it is clear there is no room for misconduct”. Conduct risk is defined as any action of a regulated firm or individual that goes against three FCA statutory objectives: to protect consumers and markets and promote competition.

Consumer Duty – this new regulatory initiative will be fully rolled out later this year and obliges all FCA-regulated firms to “set higher and clearer standards of consumer protection across financial services and require firms to put their customers’ needs first”.

Working from home – during the pandemic the FCA set out a list – still in force today – of expectations of its members around remote working, largely to ensure smooth continuity and standards around integrity, governance, customer service and employee welfare.